The Courier and Advertiser (2) – November 1966

On the eve of his departure for Australia, farmer and dance band leader lan Powrie continues the story of his life.

These grand old bothy nichts

I WAS born in 1923 – the year my father went up to Whitehouse, a farm at Strathardle, Bridge of Cally. There, he was a sort of grieve/gaffer lad. Then we moved to Maryfield, at Blairgowrie, where my sister, Mary, was born. We moved on again to Henry Thomson’s estate at Coupar Angus. That was when I started school at Bendochy. I often think about old Dominie Gibson, and my infant mistress, Miss Irvine. My two brothers, Jim and Bill, were born at Bendochy. Soon we shifted once more, this time to Essendy, between Blairgowrie and Meikleour. My youngest brother Alan was born there.

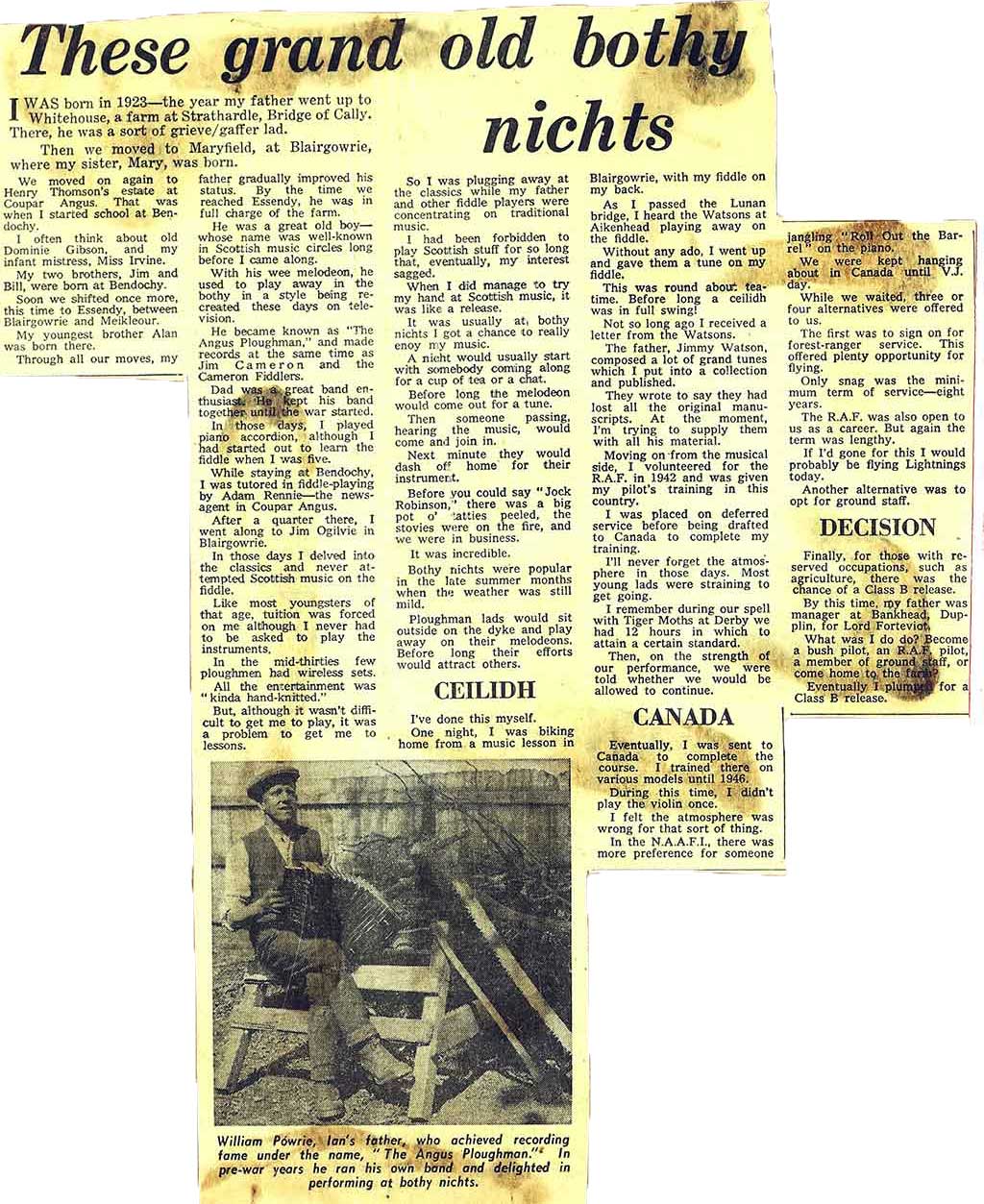

Through all our moves, my father gradually improved his status. By the time we reached Essendy, he was in full charge of the farm. He was a great old boy – whose name was well-known in Scottish music circles log before I came along. With his wee melodeon, he used to play away in the bothy in a style being recreated these days on television. He became known as “The Angus Ploughman” and made records at the same time as Jim Cameron and the Cameron Fiddlers. Dad was a great band enthusiast. He kept his band together until the war started. In those days, I played piano accordion, although I had started out to learn the fiddle when 1 was five. While staying at Bendochy, I was tutored in fiddle-playing by Adam Rennie – the newsagent in Coupar Angus. After a quarter there, I went along to Jim Ogilvie in Blairgowrie. In those days I delved into the classics and never attempted Scottish music on the fiddle. Like most youngsters of that age, tuition was forced on me although I never had to be asked to play the instruments.

In the mid-thirties few ploughmen had wireless sets. All the entertainment was ” kinda hand-knitted.” But although it wasn’t difficult to get me to play, it was a problem to get me to lessons. So I was plugging away at the classics while my father and other fiddle players were concentrating on traditional music. I had been forbidden to play Scottish stuff for so long that, eventually, my interest sagged. When I did manage to try my hand at Scottish music, it was like a release.

It was usually at bothy nichts I got a chance to really enjoy my music. A nicht would usually start with somebody coming along for a cup of tea or a chat. Before long the melodeon would come out for a tune. Then someone passing, hearing the music, would come and join in. Next minute they would dash off home for their instrument. Before you could say “Jock Robinson,” there was a big pot o’ tatties peeled, the stovies were on the fire, and we were in business. It was incredible. Bothy nichts were popular in the late summer months when the weather was still mild. Ploughman lads would sit outside on the dyke and play away on their melodeons. Before long, their efforts would attract others.

CEILIDH

I’ve done this myself. One night, I was biking home from a music lesson in Blairgowrie with my fiddle on my back. As I passed the Lunan bridge, I heard the Watsons at Aikenhead playing away on the fiddle. Without any ado, I went up and gave them a tune on my fiddle. This was round about tea-time. Before long, a ceilidh was in full swing! Not so long ago I received a letter from the Watsons. The father, Jimmy Watson, composed a lot of grand tunes which I put into a collection and published. They wrote to say they had lost all the original manuscripts. At the moment, I’m trying to supply them with all his material.

Moving on from the musical side, I volunteered for the RA.F. in 1942 and was given my pilot’s training in this country. I was placed on deferred service before being drafted to Canada to complete my training. I’ll never forget the atmosphere in those days. Most young lads were straining to get going. I remember during our spell with Tiger Moths at Derby we had 12 hours in which to attain a certain standard. Then, on the strength of our performance, we were told whether we would be allowed to continue.

CANADA

Eventually, I was sent to Canada to complete the course. I trained there on various models until 1946. During this time, I didn’t play the violin once. I felt the atmosphere was wrong for that sort of thing. In the N.A.A.F.I, there was more preference for someone jangling ‘Roll out the Barrel’ on the piano.

We were kept hanging about in Canada until V-day. While we waited, three or four alternatives were offered to us. The first was to sign on for forest-ranger service. This offered plenty of opportunity for flying. Only snag was the minimum term of service – eight years. The R.A.F. was also open to us as a career but again the term was lengthy. If I’d gone for this I would probably be flying Lightnings today. Another alternative was to opt for ground staff.

DECISION

Finally, for those with reserved occupations, such as agriculture, there was the chance of a Class B release. By this time, my father was manager at Bankhead, Dupplin, for Lord Forteviot. What was I do do? Become a bush pilot, an RAF pilot, a member of ground staff or come home to the farm. Eventually I plumped for a Class B release.

PHOTO William Powrie, Ian’s father, who achieved recording fame under the name, “The Angus Ploughman”. In pre-war years, he ran his own band and delighted in playing at bothy nichts.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.